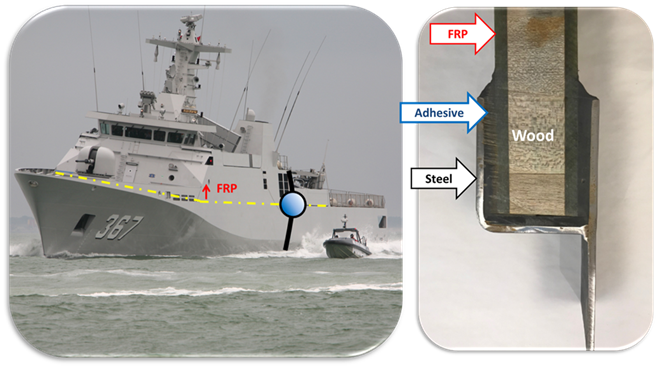

Specialists at Damen Naval are hopeful that the use of adhesives in the construction of hybrid ship structures will soon be certified by international classification societies such as Lloyd’s Register and Bureau Veritas. Recently, they have conducted many tests with the application of super strong industrial adhesives to attach a composite ship superstructure to a steel hull. The tests took place as part of the ambitious European QUALIFY project, in which not only Damen Naval but also universities and research institutes are participating.

Building a ship with a steel hull and a composite superstructure has many advantages. Firstly, you get a ship that is much lighter than one that is built completely from steel. Because the superstructure is up to fifty per cent lighter than a steel one, the ship will also be much more stable in the water. This is in addition to the advantage that its lightness reduces fuel consumption (and therefore emissions), requires a smaller engine and can sail faster. As a participant in the international QUALIFY project, Damen Naval investigated whether it is possible to make such hybrid ships that are just as strong as steel ships. In other words, they can withstand wave action, temperature differences, the effects of salt seawater, fatigue loads and other environmental factors just as well as ‘normal’ ships.

In the QUALIFY project, extensive tests were carried out to determine how a ship’s structure made of a combination of composite and steel behaves under all these conditions. The research phase of QUALIFY has now been completed and Damen Naval is entering a practical phase in the hope that the way will soon be open for international standard regulations and certification for the application of adhesive bonds in shipbuilding.

Annemarie Ruitenberg and Cedric Verhaeghe inspect one of the samples from the QUALIFY project.

Annemarie Ruitenberg and Cedric Verhaeghe inspect one of the samples from the QUALIFY project.

“We have made a start with mapping out what the classification societies want to know in order to be able to proceed with certification,” says Annemarie Ruitenberg, Specialist in Welding, Bonding and Preservation in Damen Naval’s Research & Technology Support Department. For Damen Naval as a builder of naval vessels, the QUALIFY project is all the more interesting because the weapons, sensors and communication systems (SEWACO) on frigates, for example, are located as high as possible in the ship. “That SEWACO on top of the ship weigh quite a bit of course,” explains Annemarie’s colleague Cedric Verhaeghe, Technical Specialist Composite Structures at Research & Technology Support and already involved in QUALIFY on behalf of Damen Naval since 2017.

The samples undergo extensive testing.

The samples undergo extensive testing.

Cedric: “A composite superstructure on a steel hull would not be a bad idea for a naval vessel, because it would make for a much more stable warship. The only thing is that you can’t weld composite and steel together. At least, there are hardly any regulations for such a welding method. That is why we think it is better to join these two materials using a very strong, tough, flexible industrial adhesive. That also results in a more streamlined ship, with a tighter, smoother side because no bolts; and a ship that is cheaper to maintain than a welded one.”

“A composite superstructure on a steel hull would not be a bad idea for a naval vessel, because it would make for a much more stable warship." Cedric Verhaeghe

Classification societies have handed over a so-called road map to the Damen Naval specialists, which they will use as a guideline to get ship bonding certified internationally. Damen Naval is working closely with British naval shipbuilder BAE Systems on this. “We have already gone through a very extensive course of tests and trials as part of QUALIFY,” says Cedric. “These were necessary in order to finally validate the adhesive bond as an application that is reliable and can withstand all the influences of wave movements, temperature and fatigue for a long period of time and will therefore meet all the criteria of the classification societies.”

“For example, we did an ageing test in which we kept a hybrid structure immersed in a salt water bath at a temperature of fifty degrees Celsius for twelve weeks to see if it could maintain its design strength to the end. In the same test, the actual fatigue load was measured and the structure passed the entire test with flying colours, proving to be stronger than the force with which it was loaded, and also proved to be able to withstand certain cycles of repeated loading. Together with a sensor manufacturer, we were also able to use sensors to measure and record the load of the adhesive bond in water.”

Building a ship with a steel hull and a composite superstructure has many advantages.

Building a ship with a steel hull and a composite superstructure has many advantages.

Annemarie adds: “Because we have already carried out so many tests and analyses, I think we can accelerate the road map towards certification and application of our bonding process. We’ve already done a lot of preliminary work.” Cedric: “Now that the research phase is behind us, we really hope to get the bonding process certified during an actual project. We have already built up such a sizeable dossier that additional tests will probably not be necessary.” Annemarie and Cedric therefore look back with satisfaction at the results achieved.

Hybrid warships may sail the world’s seas in the not-too-distant future, but composite is not yet available for commercial shipping due to fire safety regulations from the International Maritime Organization (IMO). So for the time being, a hybrid container ship is still in the future. As for the costs: “Compared to a steel ship, building a hybrid ship may not be cheaper, but as the life of a hybrid ship progresses, part of the investment will certainly be recouped thanks to lower maintenance costs and savings on fuel costs,” Cedric is convinced.

Annemarie is pleased that “within QUALIFY, various parties, including research institutes and universities, have shown their ability to work together very well”. She continues: “Our test results with the adhesive bonding have been excellently converted by these partners into useful information where theory and practice come together.” Cedric adds: “That combination of disciplines has produced great results. Despite the fact that Covid-19 sometimes made things more difficult, the project ultimately went very well. It is now time to test our findings in practice. International recognition and certification of our adhesive bonding is an important condition for shipbuilders to minimise risks in the construction of this type of ship.”