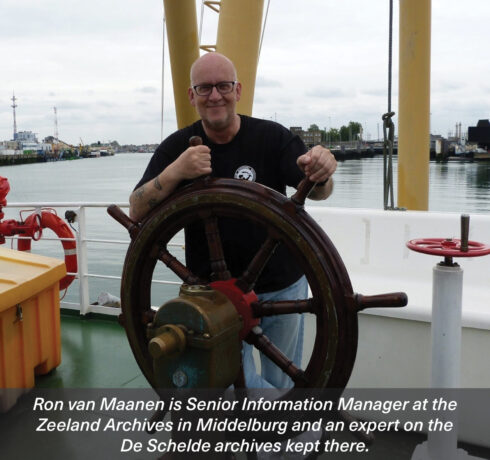

The destroyer – or rather torpedo boat hunter – HNLMS Bulhond had a hard life. When the ship was sold in 1927, after years of service in the former Dutch East Indies, its best days were over. The Bulhond was one of eight destroyers built for the Royal Netherlands Navy between 1910 and 1913. Six of the eight ships of this Wolf-class or Predator-class were built by De Schelde. The ships all served in Asia. Ron van Maanen, Senior Information Manager at the Zeeland Archives in Middelburg and an expert on the De Schelde archives kept there, has some good stories to tell about the Bulhond.

Torpedo boat hunters were actually invented to disable torpedo boats, Ron explains. Around the second half of the nineteenth century, torpedo boats were still quite primitive and not very effectively armed. “These small and fast boats were equipped with a long wooden pole on the forepeak with an explosive device attached to it, and if you rammed an enemy ship with it, it was doubtful whether your own boat would survive,” says Ron evocatively. “But the torpedo boat hunter’s armaments gradually improved and became more effective.”

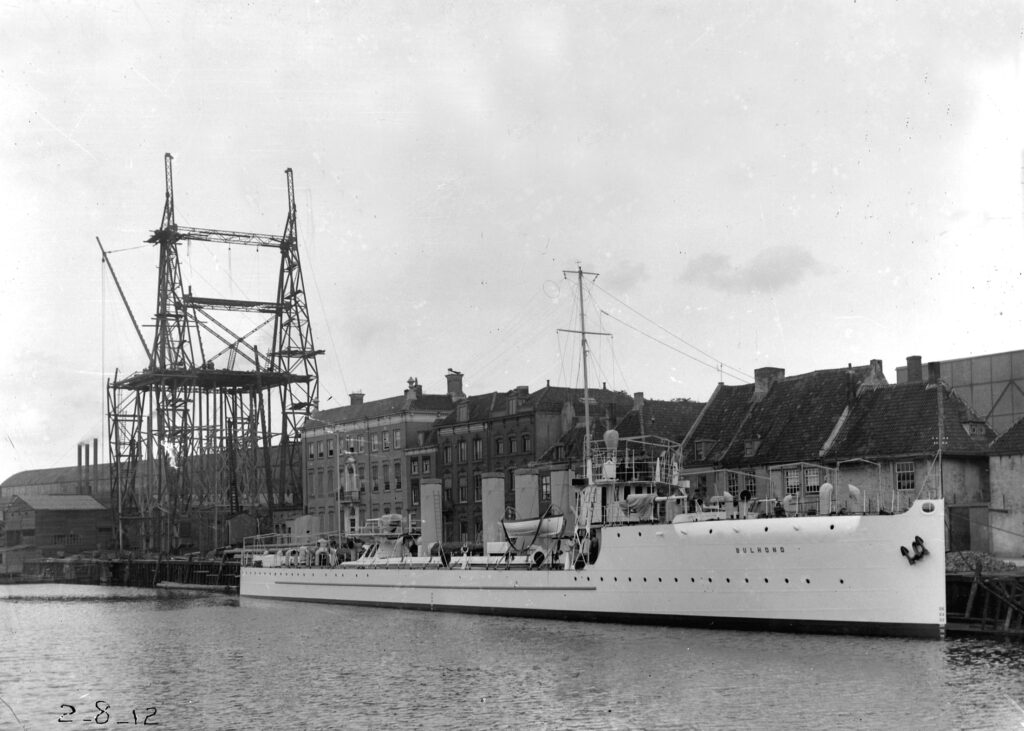

Destroyer HNLMS. Bulhond (yard number 140) is being outfitted along the Noordwal in Vlissingen.

Destroyer HNLMS. Bulhond (yard number 140) is being outfitted along the Noordwal in Vlissingen.

“Eventually they became a real danger to large naval vessels. The little boats became faster and more manoeuvrable; they circled around the big ships like sharks around they prey. Threats were only increasing, and there had to be a response. And there was, in the form of destroyers – or torpedo boat hunters – a new type of naval vessel that literally hunted down torpedo boats and tried to destroy them with cannon fire, and in later years with a combination of cannon fire and torpedoes. The Royal Schelde Shipyard in Vlissingen was allowed to build six ships of this type from 1910.

The then Dutch Department of the Navy ordered a total of eight, two of which were built by the Rotterdam shipyard Fijenoord. The Wolf-class as the series was officially called – but, in reality, mostly known as the Predator-class – consisted of the destroyers HNLMS Wolf (1910), HNLMS Fret (1910), HNLMS Bulhond (1911), HNLMS Jakhals (1912), HNLMS Lynx (1912), HNLMS Hermelijn (1913), HNLMS Vos (1913) and HNLMS Panter (1913). The last two were built by Fijenoord. “The destroyer was actually a British invention and the destroyers built by De Schelde and Fijenoord were therefore a British design,” says Ron.

Under construction at the North Slipway is Pontianak (yard number 144, renamed Deli later on), while destroyers HNLMS Bulhond (yard nr. 140) and HNLMS Jakhals (yard nr. 141) are being outfitted.

Under construction at the North Slipway is Pontianak (yard number 144, renamed Deli later on), while destroyers HNLMS Bulhond (yard nr. 140) and HNLMS Jakhals (yard nr. 141) are being outfitted.

“The specifications and the drawings came from the British shipyard in Yarrow, which was well-known at the time. De Schelde also used a British design for the successors of the Wolf-class, the Admiral-class destroyers of the 1920s.” But the choice of a British design for the Wolf-class also had to do with the close contacts De Schelde had traditionally had with English and also Scottish shipbuilders, says Ron. For example, the shipyard in Vlissingen had previously built torpedo boats that were almost exact copies of existing British models.

"HNLMS Bulhond was used extensively in the East Indies and literally sailed until the end of its days. It was constantly moving from one place to another." Ron van Maanen

The Bulhond was ordered by the Department of the Navy on 1 August 1910. It was to cost 872,950 guilders (over 396,000 euros). The construction of the 70-metre ship went without a hitch and the destroyer was launched on schedule on 20 December 1911. On 6 June 1912, the ship started her sea trials and on 29 August, HNLMS Bulhond left for Indonesia. Like the other seven destroyers, the Bulhond was powered by coal-fired engines. Ron: “The Wolf-class ships were specially built to serve in Asia, for the Dutch East Indies Defence Force as it was officially called.”

“But in retrospect, I sometimes have the idea that they were not quite suitable for deployment under tropical conditions. From the moment the Bulhond arrived in the East Indies, repairs, refurbishments and alterations had to be made to the ship. Some ships of the series also had problems with the machinery.” Ron knows that the HNLMS Bulhond had a tough life. “The ship, which could accommodate an 84-strong crew, was used extensively in the East Indies and literally sailed until the end of its days. It was constantly moving from one place to another.”

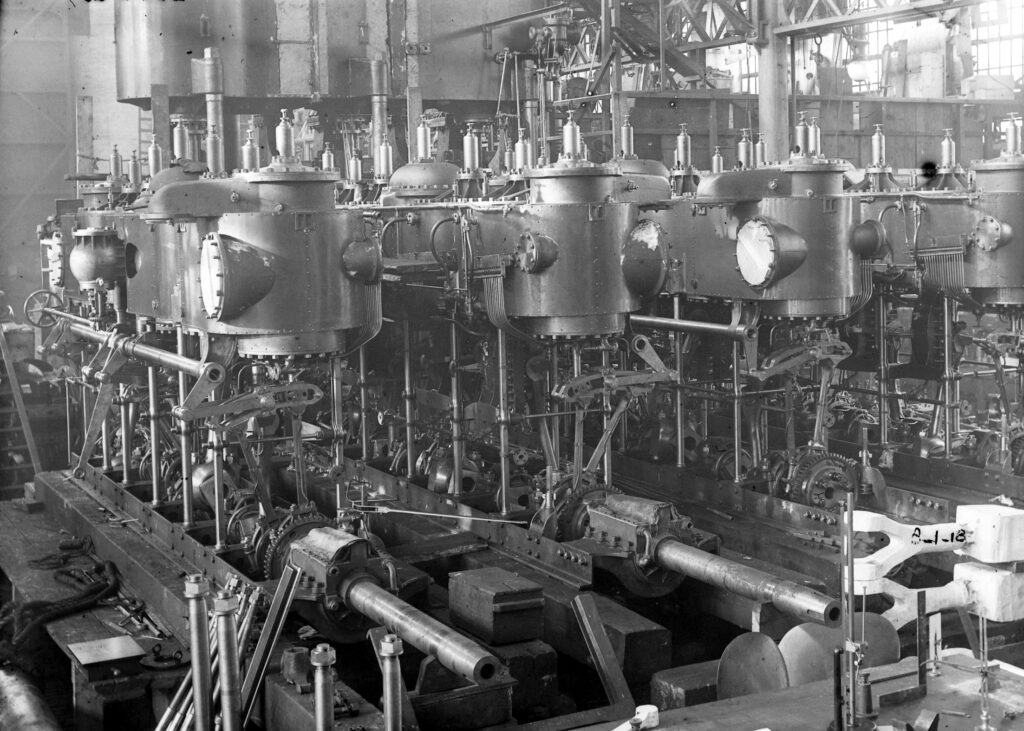

Triple expansion machines to be used on board destroyers HNLMS Bulhond and HNLMS Jakhals.

Triple expansion machines to be used on board destroyers HNLMS Bulhond and HNLMS Jakhals.

“At one point it was completely worn out. In 1927, sixteen years after being commissioned, HNLMS Bulhond was sold for 550 guilders. But by then the ship had been rusting away for a few years in a naval base in Surabaya. A salient detail is that the buyer who paid this amount of money was Japanese. Because one of the reasons for the Netherlands, actually the entire Western allied forces, to renew and strengthen its naval fleet by acquiring destroyers, among other things, was the Russian-Japanese war of 1904-1905.

“In that war, the Russian Navy suffered a crushing defeat by the Japanese Navy. That was a wake-up call for countries like the Netherlands, England, France, Germany, Portugal and the US, all of which had colonies in the East. They suddenly realised that Japan’s navy should not be underestimated.”

On 6 June 1912, HNLMS Bulhond started her sea trials and on 29 August, the ship left for Indonesia.

On 6 June 1912, HNLMS Bulhond started her sea trials and on 29 August, the ship left for Indonesia.

Why weren’t all eight destroyers of the Wolf-class built at De Schelde? According to Ron, this had to do with a secret deal that the shipyard in Vlissingen and Fijenoord had made in 1904 for the construction of torpedo boats and destroyers. With this agreement, the two shipyards wanted to prevent a situation where they would bid against each that the price would eventually be so high that the Royal Netherlands Navy would decide to go to a foreign builder. The deal stipulated that if one of the two yards won the order, the profit would be shared as much as possible. In the case of the Wolf-class order, this meant that Fijenoord was allowed to build two of the eight ships.

Torpedo boat hunters not only acted as escorts for large naval vessels, but also as armed escorts for merchant convoys on the ocean, says Ron. “In addition to taking out torpedo boats, they were also used to attack and destroy large enemy ships. The eight Wolf-class ships participated in a major military exercise in the Dutch East Indies in 1914, in which the ships worked in pairs in carrying out mock night and evening attacks on the Dutch coastal defence ship HNLMS Hertog Hendrik.”

HNLMS Bulhond in the Dokhaven in Vlissingen with the historic city hall in the background.

HNLMS Bulhond in the Dokhaven in Vlissingen with the historic city hall in the background.

“In 1924, HNLMS Bulhond participated in a search operation in the Karimata Strait and the North Java Sea for a missing ship, the Sari Borneo. The Bulhond was able to carry seaplanes and had such a seaplane on board during that search.” According to Ron, the ship was a forerunner on the subject of social inclusiveness: “The officers, non-commissioned officers and gunners on board were all Europeans, the sailors were ‘natives’, as the original inhabitants of the Dutch East Indies were called at the time. In 1915 it was decided that natives were also allowed to train as gunners.”

“These were inhabitants of the island of Menado. They were posted for service on HNLMS Bulhond and HNLMS Jakhals. In target practice, they scored just as well as the European gunners. There was one difference however: the Europeans received a bonus of between 25 and 35 guilders per six months on top of their pay, but the natives did not receive such a bonus. The European officers then decided to pay part of that premium to the natives out of their own pockets.”