Damen Naval's Herman Vermeulen (with hat) and John Akihary working a QUALIFY sample at Vlissingen-East.

Damen Naval's Herman Vermeulen (with hat) and John Akihary working a QUALIFY sample at Vlissingen-East.

Can we build seagoing vessels with composite superstructures? These would have to be firmly attached to the hull. The European Union is supporting a major international project that is investigating whether it is possible to attach a composite superstructure to a steel hull with glue so strong that the construction would last for at least a quarter of a century.

Damen Naval is participating in the project. In QUALIFY, numerous parties are investigating the feasibility of fabricating large scale primary shipbuilding structures consisting of a combination of composite plastics and steel. Cedric Verhaeghe is closely involved.

The aim of the research is to reach the point when the adhesive joints used for such structures meet the requirements for certification from international classification societies. Cedric has been participating in QUALIFY since the project started (at the end of 2017). He explains that small vessels are already being built from a combination of composite and steel. “QUALIFY investigates mainly the long-term behaviour of the adhesive bond used to connect the plastic superstructure to the steel hull – which is under the influence of the variable forces of the sea state, the effect of salty seawater, temperature differences and other factors.”

Besides Damen Naval, the British naval vessel builder BAE Systems, wind energy company Parkwind and the research institutes Com&Sens, M2i and Sirris, as well as the universities of Ghent and Cambridge and TU Delft are participating with the project too. It is of particular importance that the classification societies Lloyd’s Register and Bureau Veritas are also involved in the research. However, these agencies do not yet have guidelines for the use of glues in large ships. “With QUALIFY, we hope to validate adhesive bonds for a period of 25 years,” says Cedric.

“The two classification societies are observing our work and will come up with draft guidelines at the end of this year. This can serve as a basis for formulating the regulations that will certify the use of glue.”

QUALIFY is an EU Interreg 2 Seas project, in which the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Great Britain are cooperating. Damen Naval supplied the samples with which to test the adhesive joints. These were fabricated in a production hall in Vlissingen-East. Cedric: “We also formulated the preconditions and operational requirements for the tests and simulations with the adhesive bonds. As a shipbuilder, you try to ensure throughout the entire process that there is always a relevance with the reality of an operational ship.”

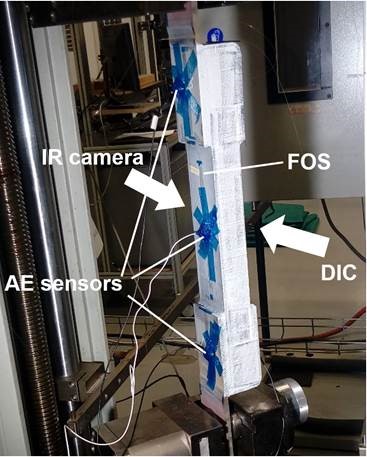

A “full scale” test sample showing a number of the measurement techniques used by Damen Naval.

A “full scale” test sample showing a number of the measurement techniques used by Damen Naval.

Starting off with smaller sized samples, Damen Naval also started testing full-scale samples over the course of last year. “We lowered the plastic part into a steel gutter in a connecting piece cut between the superstructure and the hull. The glue was injected into the material via small holes. The most important aspect is the interaction between the composite and the steel – and how the glue behaves. Using optical glass fibres that registered distortions, we could study this in-situ.”

The University of Ghent, Belgium is currently studying the results of the full-scale tests.

“Analysis of small and medium scale tests have already shown that the adhesive bond is so strong that it can withstand a variety of stresses for at least 25 years,” continues an enthusiastic Cedric, who works in Damen Naval’s Engineering Department as Senior Engineer with Research & Technology Support. He finds the QUALIFY project “very nice to work on”. “I hope that we will get more and more familiar with the use of glue so that, as well as non-primary applications, we can also use it for large parts of a ship, such as the superstructure. When building such hybrid ships, the superstructure can be made 50 per cent lighter, making the entire ship 10 per cent lighter.”

“This has direct consequences on the propulsion: you use less fuel and therefore produce less harmful emissions. The stability also increases, so that the rest of the ship can also be made with lighter materials. The hull will still be made of steel, but it can be narrower and smaller, so that the ship will produce even less emissions.”